Guam’s high cost of living is not just a topic for discussion — it’s a reality every person on the island lives with. For some, it’s an inconvenience. For others, it’s a constant source of stress.

It wasn’t the only reason my family moved to the mainland two years ago, but it was part of the equation. Both my husband’s and my siblings and mothers live off island, and visiting them meant airfare bills that could reach nearly $10,000 for five people. Anyone who’s tried to “make every dollar count” on a family trip from Guam knows the drill: jam-packed itineraries, exhausting travel, constant calculations about whether the visit is worth the cost — and loading up on strawberries, blueberries, peaches, and other fruits simply because they’re less than half the price we’d pay at home. I know thousands of you have your own version of this story.

As our mothers age, and as we also are aging, we wanted to be closer — and more accessible. In the last two years, the most we’ve paid for a plane ticket was about $800, when Steve decided at the last minute to help care for his mom after surgery.

The difference between living in Guam and living in Northern Virginia is night and day. Groceries, utilities, telecom bills, even business expenses — here, they’re at least half the cost of Guam, if not less. That makes me sad, because I know how hard it is for families on Guam making the median household income of $58,289 or less — and half of all households earn below that. For those families, every dollar stretches painfully thin.

The everyday math of living on Guam

According to Numbeo, which tracks cost-of-living data globally, common grocery items in Guam cost far more than U.S. averages:

Milk: +212%

Bread: +62%

Eggs: +37%

Apples: +53%

Bananas: +85%

The information is according to NUMBEO, founded by a former Google employee, crowdsourced and based in Belgrade. I can vouch for those numbers. Paying more than $13 for a gallon of milk before we left — versus about $3 here — is still a shock.

And that’s just groceries. Guam’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) shows prices have risen 71% since 2007 and 30% since 2019 — double the U.S. mainland’s 15 to 20% increase over the same period. The All Items CPI went from 131.8 to 171.4 in five years.

Purchasing power tells the rest of the story: In 2019, $1 bought what about $0.76 bought in 2007. Today that dollar buys just $0.58. Everyday costs are roughly a third higher than before the pandemic, and your dollar now stretches about one-fifth less.

Wages haven’t kept pace.

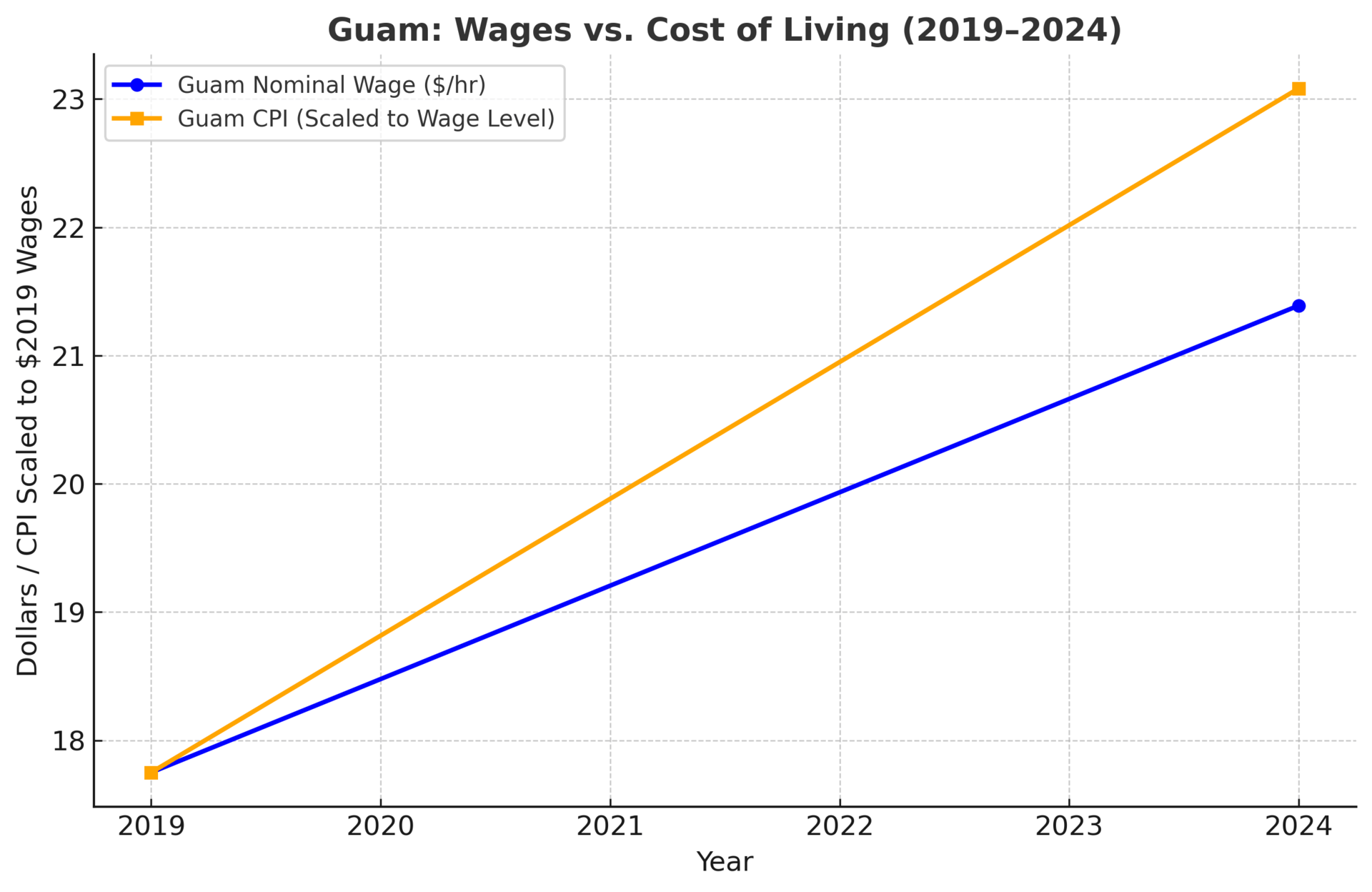

From 2019 to 2024, Guam’s nominal wages rose from $17.75/hour to $21.39/hour — a 21% increase. But with prices up 30%, real wages — what your pay can actually buy — fell about 7.3%.

In contrast, the average U.S. worker saw nominal wages rise 27% in the same period, with prices up about 21%, leaving a small 4.5% gain in purchasing power.

The chart tells the story: one line for wages, one line for CPI. Both go up, but CPI climbs faster. Bigger paychecks in dollar terms, but less buying power.

If these trends continue, the risks are real.

We could see more skilled workers leaving for higher-paying jobs on the mainland, eroding the island’s talent base in critical fields like healthcare, utilities, and science. We could see greater dependence on social services, which the government — and taxpayers — will have to fund, even as the tax base shrinks.

Already, SNAP benefits reach more than 33,000 people on Guam, costing roughly $11 million a month. Medicaid, housing assistance, and other safety-net programs add to the pressure. Rising everyday costs could also make stable housing less attainable for many families, if it isn’t already.

I think often about that $13 gallon of milk, and how much of my decision to leave was wrapped up in daily calculations like that. For thousands of families still on Guam, those calculations never stop — every trip to the store, every utility bill, every holiday ticket home is a choice between what they want and what they can afford. That is no way to live long term.

The trends are clear: without intervention, the cost of living will continue to rise faster than wages, deepening the strain on households and government resources alike. The question is not whether we can afford to act, but whether we can afford not to.